IN THIS LESSON

Understand what dot products represent conceptually.

1/4/25: This entire “course” (more like section) is very incomplete at the moment and only includes this lesson. I intend to add more in the near future.

Mathematical Explanation:

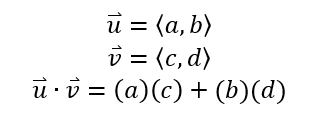

At its core, a dot product is simply a mathematical operation. They take two (or more) vectors and produce one scalar quantity. The purely numerical explanation of this concept is as follows:

Note: is a type of vector notation, called component notation. Another type of vector notation, called unit vector notation, is what we’ve been previously using in class, and uses unit vectors î and ĵ to represent the horizontal and vertical components of a vector. Component notation is very similar; the first value represents the horizontal component and the second value represents the vertical component of a vector.

In physics, as we are currently learning, dot products of vectors can be applied to quantify the amount of work done by a force vector over a displacement vector.

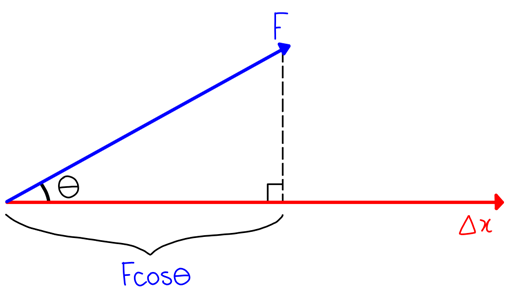

Work can be defined as either of these two equations:

We’ve been primarily using the second equation to compute work, since we are not as familiar with dot products. However, we can use this second definition to understand why the first equation makes sense for this concept.

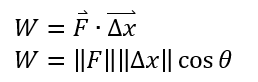

In calculus, dot products are used to determine the angle between two vectors, using the properties of the dot product with the geometry concept of the Law of Cosines.

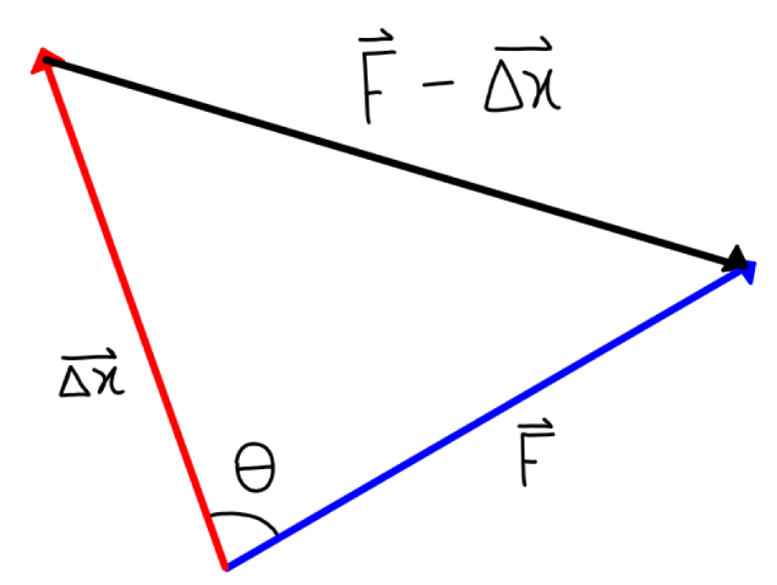

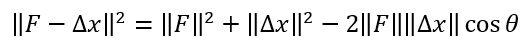

The Law of Cosines, using the diagram above for reference, says that:

The properties of dot products that we will use for this proof state that:

Dot products are commutative: u ⋅ v = v ⋅ u

Dot products are distributive: u ⋅ (v + w) = u ⋅ v + u ⋅ w

A vector dotted with itself is equal to its magnitude squared: u ⋅ u = ||u||²

So, with these concepts in mind, here is the final proof that our two definitions of work are equivalent (F ⋅ Δx = ||F||||Δx||cos(θ)), using the diagram below:

By the Law of Cosines:

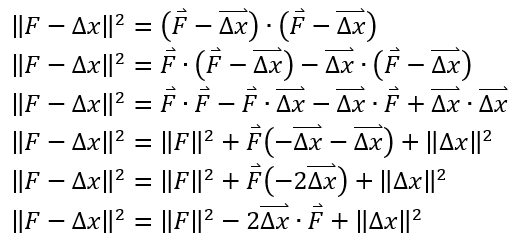

Using the properties of dot products, we can rewrite ||F - Δx||²:

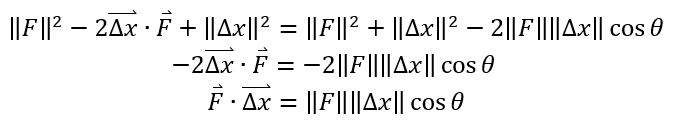

And then we can plug this expression back into the Law of Cosines equation and simplify:

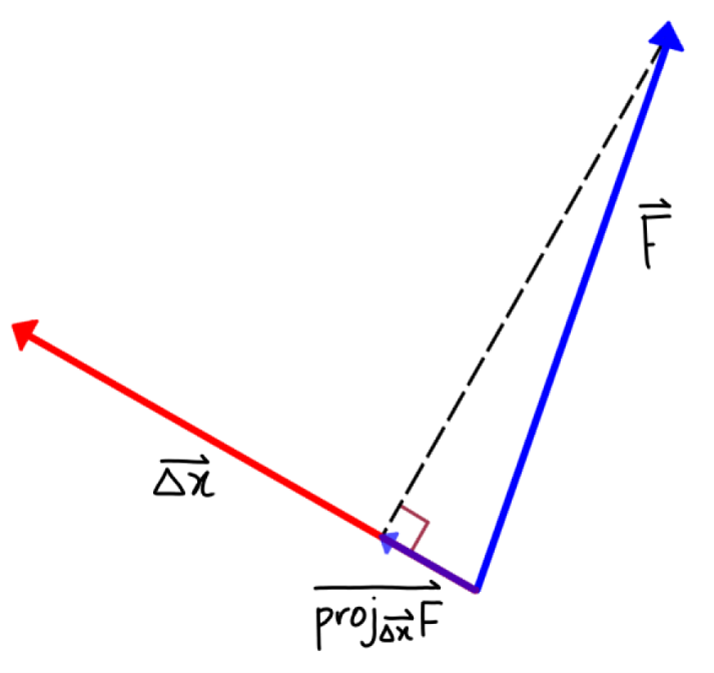

So, as we can see, these two equations for work are equivalent to each other, and therefore the concept of the dot product in this scenario is just a different way to express work. To understand why this is true, we can use the concept of projected vectors. This is a much higher-level concept than what we need for this lesson, so this will be a very simplified explanation. Essentially, as we’ve learned, dot products multiply the magnitude of one vector by the magnitude of the component of the other vector that is parallel to itself. Vectors that are “closer” in direction produce higher dot products. A projected vector is the component of one vector that is parallel to the other vector being dotted, as shown in the diagram below:

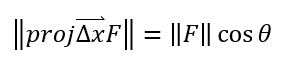

For our purposes, we achieve this “projection” by multiplying our force vector by the cosine of the angle between our force vector and our displacement vector. This gives us the force vector projected onto the displacement vector, or the component of the force vector that is parallel to the displacement vector. So:

A dot product is the magnitude of a vector (a scalar quantity) multiplied by the magnitude of another vector projected onto the first vector (another scalar quantity), which produces a scalar quantity, which, in our case, is the same as the magnitude of the displacement vector times the magnitude of the force vector multiplied by the cosine of the angle between the two vectors.

Conceptual Explanation:

Conceptually, how can we “multiply” two vectors and produce a scalar quantity, and in physics, how does that quantity represent work? It’s a very difficult concept to describe, but I’m going to try my best to put it into words.

1 - The dot product is a scalar quantity because, in a literal sense, it is a measure of how closely two vectors align, in terms of direction. The “closeness” of two vectors does not have a direction, so it is a scalar value.

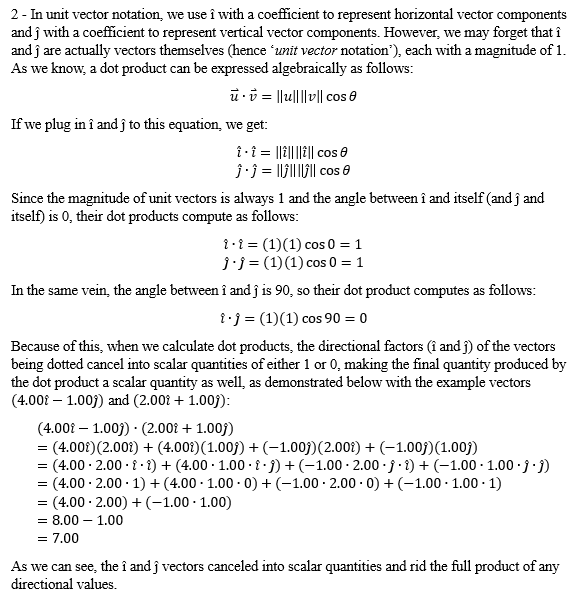

Note: the special characters were so difficult to transfer from my original document that I chose instead just to screenshot and insert that here. I apologize for the low quality image. You may view the full document by clicking the button at the bottom of the page.

3 - The two main pieces of work as a concept are a force and some displacement. The value we use to account for the force is the (scalar) amount of force that is going into the direction of the displacement vector. This is where we use the expression , where we are multiplying two scalar quantities (the magnitude of a force vector and a cosine) to find that amount. The units we use for this value are Newtons because the value is still the magnitude of a force, which is always expressed in Newtons. Next, we find the (scalar) magnitude of the displacement vector, because work specifically transfers energy from one location to another (the energy is displaced). The units we use for the magnitude of displacement are meters because, once again, the value still represents a measured movement of some kind, which we always express in meters. Therefore, the two quantities we account for in finding work are both scalar, and therefore, produce a scalar product. In the same vein, multiplying scalar amounts of Newtons by meters produces Newton-meters, otherwise known as Joules, which are the units we use for work.

Combining these three explanations can help us start to understand why work is a scalar and what it represents in physics.