IN THIS LESSON

Learn how to represent atoms, molecules, and chemical bonding visually.

1/4/25: I consider this lesson complete right now, but I intend to redraw the diagrams to be of higher quality.

Electron dot diagrams (aka Lewis Dot Diagrams or LDDs) depict valence electrons of atoms. They can also depict how valence electrons of different atoms interact with each other.

Valence electrons are the electrons in the s and p subshells of the outermost shell of electrons of an atom. In noble gas notation of electron configuration, they are the “leftover” electrons after the noble gas is written.

For example:

The electron configuration of sodium (Na) is written as [Ne]3s¹. Sodium has one valence electron.

The electron configuration of silicon (Si) is written as [Ne]3s²3p². Silicon has four valence electrons.

Atoms form bonds when they have orbitals that are not full, usually in their valence shell. This causes atoms to be unstable. In the case of covalent bonds, they fix this problem by overlapping their valence electrons with valence electrons of other atoms, forming pairs that they can both use to fill their orbitals.

LDDs show the valence electrons as four pairs of electrons around an element symbol. For later purposes, these pairs represent the orbitals in the s and p subshells of the valence shell of an atom.

For example:

Neon (Ne) can be represented by this LDD:

Rules of drawing LDDs:

Electrons are drawn on four sides of the element symbol.

There cannot be more than two electrons on each side.

There must be one electron per side before they can double up.

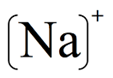

LDDs of ions:

Brackets are placed around the element symbol and electrons that are drawn. The charge is placed outside the bracket.

For example:

A sodium cation (Na⁺) can be represented by this LDD:

A full outer shell for elements other than hydrogen and helium follows the octet rule. This rule states that when an atom has eight valence electrons that it either owns completely or shares with another, it is stable.

Ionic compounds will lose or gain electrons to have eight (or two) valence electrons total. Ions with equal and opposite charges will attract together.

For example:

Sodium (Na) loses an electron to become a cation (Na⁺). Chlorine (Cl) gains an electron to become an anion (Cl⁻). Since these charges are equal and opposite, they will bond ionically.

Magnesium (Mg) loses two electrons to become a cation (Mg²⁺). Chlorine (Cl) gains an electron to become an anion (Cl⁻). Though these charges are opposite, they are not equal. To properly balance the charges, one Mg²⁺ ion will bond to two Cl⁻ ions.

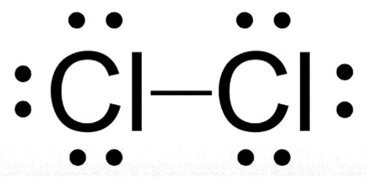

Ionic bonds are not shown through LDDs, while covalent bonds are.

Covalent bonds can be shown by having a pair of dots (representing a pair of electrons) between two element symbols that are sharing electrons. They are more often shown as a line connecting the two element symbols that represent the bonded atoms. The lone electron pairs are still shown around the element symbols for the atoms they are apart of. Lone electron pairs are pairs of electrons that only belong to one atom.

For example:

H₂ is represented by this LDD:

Cl₂ is represented by this LDD:

Atoms can bond to each other more than once, forming double or triple bonds. These are formed covalently with more than one electron pair connecting two atoms.

For example:

O₂ is represented by this LDD:

Coordinate covalent bonds occur when both the electrons in a covalent bond are contributed by one of the two atoms. They are represented by arrows pointing from the atom that contributed the electrons to the other atom.

For example:

The LDD of SO₂ can be drawn through these steps:

General steps for drawing LDDs:

Establish the “center” atom(s). This atom is usually listed first in the chemical formula or is the element with the least atoms. It is usually N, S, or C.

Establish the “end-of-the-line” or terminal atoms. These are usually H, O, or a halogen.

Unpaired electrons usually form bonds. Draw bond lines between unpaired electrons of adjacent atoms.

Count the number of total valence electrons of all the atoms in the compound. It should be the same as the total valence electrons of all atoms in the compound before you began drawing bonds. Remember that a bond line represents two electrons. The only exception to this rule is polyatomic ions, however we don’t have to deal with drawing those in this unit.

Resonance hybrids are used when multiple LDDs can be drawn to represent the same compound. These LDDs can have very minimal changes between them, but it still matters to consider all of them as these small factors can have large effects.

For example:

Benzene rings contain six carbon atoms with three double bonds and three single bonds forming them all into a ring, with the different types of bonds alternating around the ring. Although the structure technically remains the same when the single and double bonds are drawn in different places on the rings, it still matters that this factor can be different. Previous experimentation has also shown that the length of the bonds in benzene rings are all equivalent, which would be incorrect if each bond was either a single or a double. This shows that each bond is a hybrid, or a sort of average or in-between version of a single and a double bond.

Main points about resonance hybrids:

Electrons don’t actually resonate, or flip back and forth, between types of bonds. The reality is that they exist as a middle ground between the two types.

These are used as an alternate tool to LDDs because LDDs are tools that cannot always be used.

Expanded or Shrunk “Octets”

Some atoms are small enough to accommodate less than eight valence electrons and still be stable (e.g. boron (B)). Others are large enough to accommodate more than eight valence electrons. These are usually non-metals that are larger than neon (Ne). In this unit, we don’t have to identify which elements or compounds follow this pattern, however if given a chemical formula that does, we should know how to recognize this it.

Free radicals are another exception to the octet rule. They are molecules that contain an odd number of valence electrons.

For example:

NO has five valence electrons from nitrogen and six valence electrons from oxygen, adding up to eleven total.

These molecules are unable to follow the octet rule. They are highly reactive and dangerous; they can destroy tissue and cause cancer and death.